The Historic Pardon Of A Convicted Man In Nebraska Was A Century In The Making

We like to think that we’ve got this whole justice system figured out, but the truth is that sometimes, the unthinkable happens and an innocent person is convicted and jailed. People in the late 19th century didn’t have the technology we have today, so the likelihood of mistakes by the investigators was much higher than it is now.

Marion, his wife, and his friend John Cameron were staying with the wife's mother in Liberty, Nebraska. The men planned to travel west to work on the railroads.

One spring morning in 1872, Marion and Cameron set off to start their work with St. Joseph and Denver City Railroad, stopping in Beatrice on the way. It was only a few days before Marion unexpectedly returned to his mother-in-law's home in the middle of the night. He showed up with Cameron's belongings, but Cameron himself was nowhere to be seen. Marion said that Cameron had sold all of his things to Marion, then left to visit his uncle in Kansas.

One spring morning in 1872, Marion and Cameron set off to start their work with St. Joseph and Denver City Railroad, stopping in Beatrice on the way. It was only a few days before Marion unexpectedly returned to his mother-in-law's home in the middle of the night. He showed up with Cameron's belongings, but Cameron himself was nowhere to be seen. Marion said that Cameron had sold all of his things to Marion, then left to visit his uncle in Kansas.

Marion's wife and her mother were the first to point the finger at the man and accuse him of killing Cameron. Soon, the entire town had heard their story and grew suspicious of the man from a different state. Marion's father saw the town's ire growing and told his son that if he was guilty, he should run far away. The younger Marion took off and wasn't seen again for a decade.

A year after Marion's departure, a corpse was found in a ditch on the Otoe Reservation in Gage County. It was wearing what appeared to be the same clothing Cameron was wearing on the day of his disappearance. And, most importantly, there were three gunshot holes in the skull.

A year after Marion's departure, a corpse was found in a ditch on the Otoe Reservation in Gage County. It was wearing what appeared to be the same clothing Cameron was wearing on the day of his disappearance. And, most importantly, there were three gunshot holes in the skull.

Advertisement

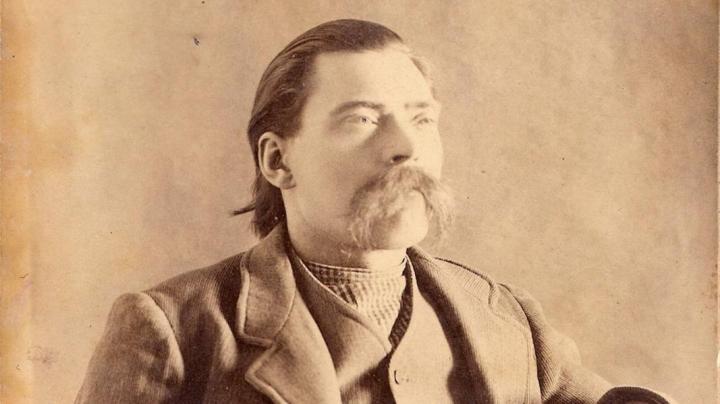

Marion was promptly arrested by Nathaniel Herron, the then-sheriff of Gage County. When they got to Beatrice, Marion sat in a jail cell for four long years as he awaited trial. The trial lasted for two months and resulted in Marion's conviction.

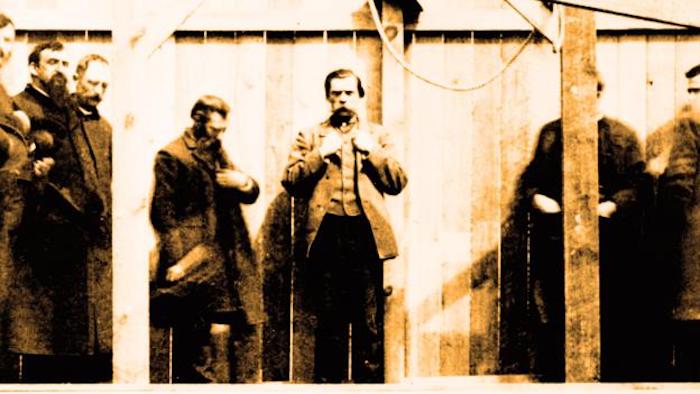

After winning an appeal on a technicality, he was tried again...and again, a jury convicted him and sentenced him to death by hanging. A small but dedicated group of people tried in vain to stop his execution, pointing out that there was no evidence proving that Marion killed Cameron, or even that Cameron was dead at all. They alleged that the guilty verdict and death sentence resulted not from a man's death, but rather from the bloodlust and morbid fascination of the public.

Marion was denied a second appeal and was hanged on March 25, 1887. Just before his death, he was reported to have said "I confess that I am a sinner, the same as any other law-abiding citizen or church member. … All I have to say is God help everybody." His body was buried in an unmarked pauper's grave.

After winning an appeal on a technicality, he was tried again...and again, a jury convicted him and sentenced him to death by hanging. A small but dedicated group of people tried in vain to stop his execution, pointing out that there was no evidence proving that Marion killed Cameron, or even that Cameron was dead at all. They alleged that the guilty verdict and death sentence resulted not from a man's death, but rather from the bloodlust and morbid fascination of the public.

Marion was denied a second appeal and was hanged on March 25, 1887. Just before his death, he was reported to have said "I confess that I am a sinner, the same as any other law-abiding citizen or church member. … All I have to say is God help everybody." His body was buried in an unmarked pauper's grave.

Advertisement

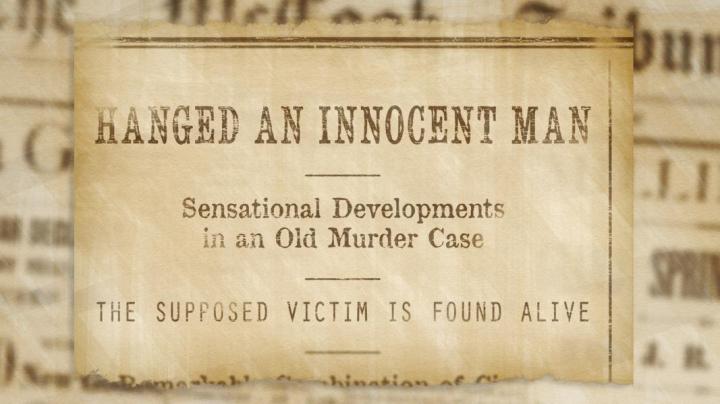

The case more or less passed from the minds of the public for the next four years. In 1891, the last person anyone ever expected to see again resurfaced. It was John Cameron, alive and well, adding another chapter to this tragic story. He said that he had been traveling all over for the past nearly 20 years and hadn't heard of Marion's arrest, conviction, and hanging until Marion's uncle went looking for him in Kansas. Cameron wrote a statement confirming that he was, in fact, alive, and sent it back to Beatrice with the uncle.

Cameron explained that Marion had been telling the truth: he sold his horses to Marion, left most of his belongings behind, and fled town to avoid a paternity allegation. He still carried the IOU Marion had written for the remainder of his purchase. On his way out of the area, he had traded clothes with a Native American man, which would explain why the corpse found in a ditch on the reservation was wearing his clothes.

Cameron explained that Marion had been telling the truth: he sold his horses to Marion, left most of his belongings behind, and fled town to avoid a paternity allegation. He still carried the IOU Marion had written for the remainder of his purchase. On his way out of the area, he had traded clothes with a Native American man, which would explain why the corpse found in a ditch on the reservation was wearing his clothes.

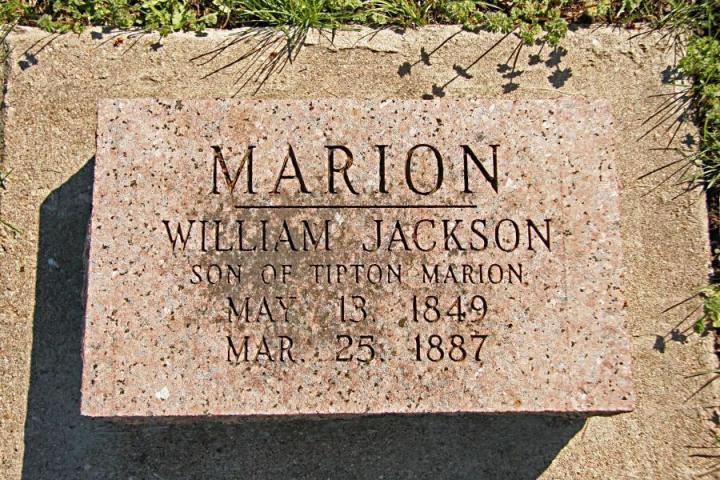

Marion's great-grandson did years of research, uncovering ample evidence of William Marion's innocence. The great-grandson, Elbert Marion, petitioned then-Governor Bob Kerrey to pardon his ancestor. On March 25, 1987, 100 years to the day after he was executed, Marion was posthumously pardoned.

The simple marker bears his name, his father's name, and his birth and death dates. Most interestingly, Governor Kerrey's pardon is framed and sealed in plastic next to the marker. The document is a chilling reminder that sometimes the legal system doesn't work as it's supposed to. It's also a testament to the strength of family bonds and the determination of Marion's descendants.

Had you ever heard William Jackson Marion’s tragic story?

For another true crime story from Nebraska, check out this article about the largest mass murder in the state which is still unsolved.

OnlyInYourState may earn compensation through affiliate links in this article. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

Featured Addresses

Beatrice, NE 68310, USA